Auroras are usually visibly above polar regions but during intense geomagnetic storms the spectacle intensifies and can be visible from farther afield.

The sun is waking up and we are experiencing the effects on Earth as disruptive radio blackouts and stunning aurora displays.

Yesterday’s flare was reported to have caused some disruptions to GPS signal and interference with high frequency radio transmissions, which are used by shortwave broadcasting stations, aviators and radio amateurs.

“X-1.35 Flare! Region 2975 fires again with a possible Earth-directed #solarstorm too!” Tamitha Mulligan Skov, a space weather researcher at the Aerospace Corporation said on Twitter. (The 1.35 refers to the strength of the X-flare, indicating it was a relatively weak one.) “Expect waning #RadioBlackout & #GPS reception issues near dawn & dusk over next hour especially for USA, Canada, S.America, Hawaii, W. Africa & W.Europe.”

As sunspot 2975 continues its temper tantrums, further disruptions are possible in the coming days. For Thursday (March 31), the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) forecasts a 50% risk of minor to moderate radio blackouts. On Friday, April 1, the risk will go down to 35%. Both days have a 10% chance of a strong radio blackout, which could cause wide-spread disruption to high frequency radio communications on the sun-facing side of Earth, with a possible hour-long loss of signal.

A strong radio blackout (R3 on NOAA’s five-point scale) is a relatively common occurrence that can take place up to 2,500 times over the sun’s 11-year cycle of ebbing and flowing activity, according to NOAA.

Although communications blackouts can be disruptive, the more sluggish outbursts called coronal mass ejections, or CMEs, that have accompanied some of the recent flares are raising the chances of catching breathtaking aurora displays for those living in the northern parts of America and Europe, as well as New Zealand in the Southern Hemisphere.

CMEs are expulsions of magnetized plasma from the upper layers of the sun’s atmosphere, the corona. When a CMEs hits Earth, it may temporarily disrupt the planet’s protective magnetic field. When that happens, the plasma particles penetrate deep into Earth’s atmosphere, where they trigger magnetic storms that produce colorful aurora displays. These auroras generally happen near the poles as the magnetic field is the weakest there, allowing the solar particles to sink deep into the atmosphere. The more powerful the geomagnetic storm, the farther away from the poles the spectacle can be observed.

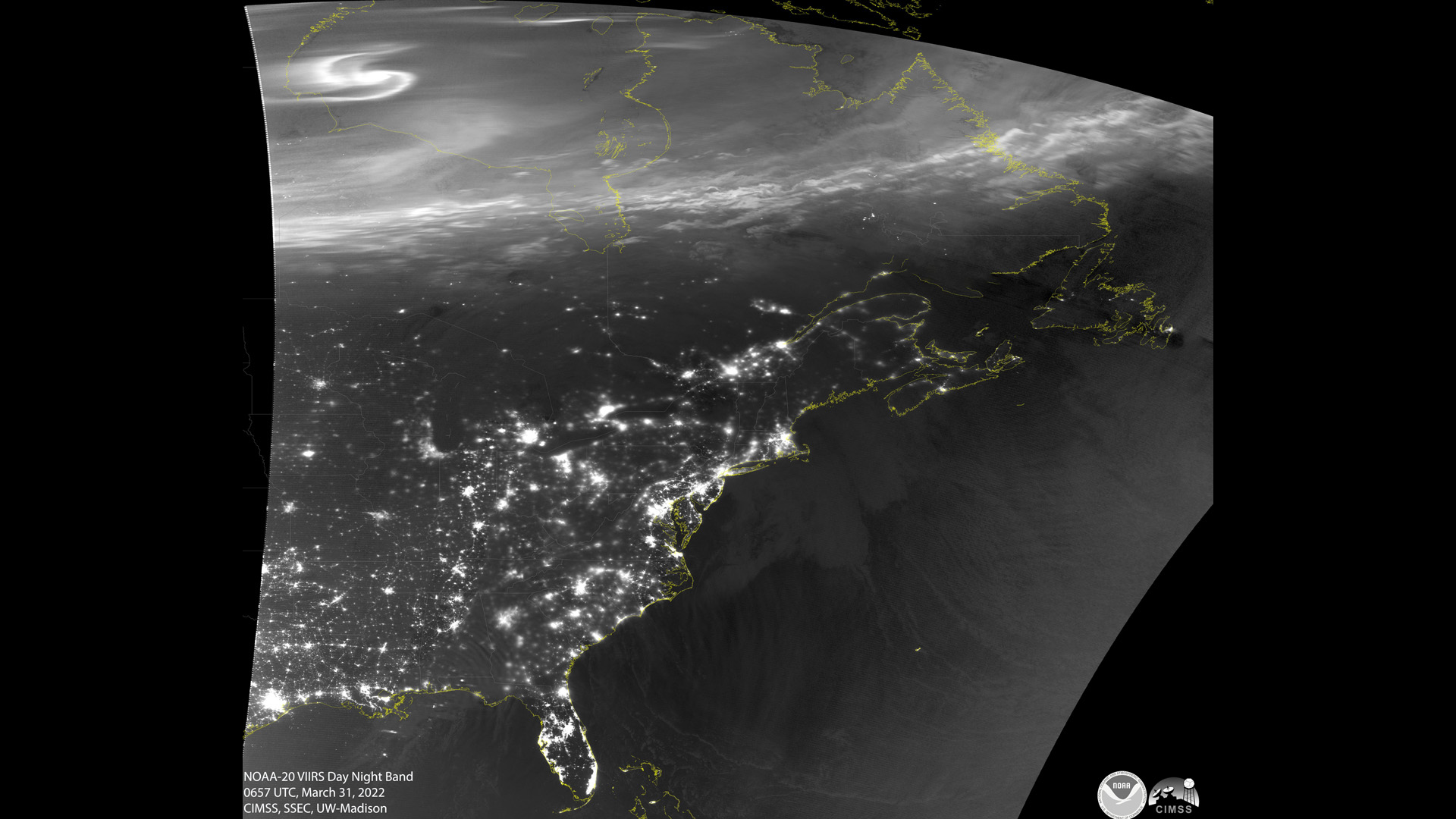

Two CMEs the sun blasted out on Monday (March 28) arrived yesterday night (March 30), delivering aurora viewing opportunities all over Canada, with reports also coming from North Dakota and even as far south as Colorado.

NOAA’s polar-orbiting NOAA-2 weather satellite snapped a black and white picture of auroras above the North Pole after a powerful geomagnetic storm hit Earth on March 30, 2022. (Image credit: NOAA)

“1st test shot shows #aurora showing up on camera already before 10pm MST down to Paradox Valley Colorado currently!” Twitter user Derick Wilson tweeted on Wednesday night.

In the Southern Hemisphere, skywatchers from New Zealand and Tasmania also reported seeing the polar lights.

And there might be more to come. The geomagnetic situation around Earth is expected to become still more turbulent throughout Thursday and Friday, with a 30% possibility of a strong geomagnetic storm (G3 on a five-point scale) and even a 10% risk of a G4 storm, according to the U.K. national weather forecaster Met Office. Met Office personnel forecast “disturbed geomagnetic conditions” on Friday and that “unsettled” conditions may remain through Sunday (April 3).

In addition to auroras, a G3 and G4 geomagnetic storm could cause minor problems to satellites in orbit and power networks on Earth.

The Wednesday X-flare also produced a CME, which is currently being analyzed “for any Earth-directed component,” Met Office said in the statement. The agency also noted that further moderate-class flares are possible in the upcoming days.

The sun’s activity has only recently picked up after a prolonged minimum during which it sported virtually no sunspots. The star is still relatively sleepy, but its activity is expected to increase gradually as we head toward the next solar maximum, predicted to occur around 2025.