This fantastical creature highlights the continuities that extend over centuries of food technology and culture.

Number one, vegetarians—or those easily grossed out—should not scroll down. You’ve been warned.

Food is sustenance and nutrition, but it is also art and entertainment and provocation and worship (see: bacon, Thanksgiving).

So, if the people and activities and foods of the past seem impossibly strange to you… Look around. We’re the ones who create portraits of the actor Kevin Bacon made of bacon. Imagine what your great grandkids will think of that as they eat their drone-farmed GM organic carrots on the formerly arctic plain.

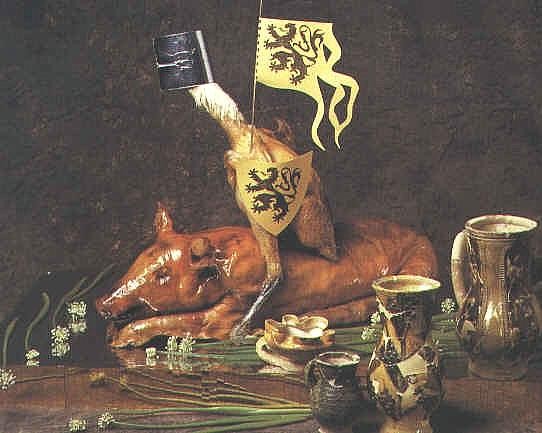

In any case, the good people of early modern Europe, roughly the period from 1500-1800, had their own peccadiloes. And one of those was sewing together chimerical animals and then eating them. Which brings us to this photograph:

This is a real image shared with me by Richard Fitch, the project coordinator for the Historic Kitchens at Hampton Palace, which once served meals to the court of the notoriously gluttonous Henry VIII.

Fitch calls himself an experimental historian. He makes the foods described in the cookbooks of yore; his site is called Cooking the Books.

The specimen above is called a cockentrice (or cockentryce). It is, quite literally, a pig’s upper body sewn onto a turkey bottom. The recipe for it dates from the 15th-century, although it was known to be made in later years. Here’s how one source describes what to do (a capon, FYI, is just a big chicken):

Cockentrice – take a capon, scald it, drain it clean, then cut it in half at the waist; take a pig, scald it, drain it as the capon, and also cut it in half at the at the waist; take needle and thread and sew the front part of the capon to the back part of the pig; and the front part of the pig to the back part of the capon, and then stuff it as you would stuff a pig; put it on a spit, and roast it: and when it is done, gild it on the outside with egg yolks, ginger, saffron, and parsley juice; and then serve it forth for a royal meat.

Fitch, true to the recipe, also created the poultry head-pig behind combination, too. Here it is roasting on a spit:

There is a variation on this dish called the Helmeted Cock in which the bird is made to ride the pig in military regalia.

These dishes are not even the most technically complex dish that was served to the royals of the era. During long meals, certain dishes called subtleties (or entremets) were often presented. The dishes themselves were supposed to be entertaining, and they sometimes included actual entertainment.

One dish, Rôti Sans Pareil, must be considered the direct ancestor of the modern turducken, though it bears the sort of relationship that Methuselah would have with modern centenarians.

Because the “Roast Without Equal” was formed by stuffing 17 birds inside each other like Russian dolls! Seventeen engastrated birds! In order, they were:

- Warbler

- Bunting

- Lark

- Thrush

- Quail

- Lapwing

- Plover

- Partridge

- Woodcock

- Teal

- Guinea Fowl

- Duck

- Chicken

- Pheasant

- Goose

- Turkey

- Giant Bustard

(Note that our modern variants swap the duck and chicken positions.)

Now, it is fair to ask why such dishes would be made.

First, why these specific creatures: why the chimeras? There are many answers, I’m sure. The European discovery of the Americas with their many strange new animals might have made anything seem possible. The Renaissance-inflected desire to look back to the Classical civilization with its many animal (and human-animal) hybrids might have made such combinations seem more clever, too.

And the scholars Miguel de Asua and Roger French note that Europeans connected the Classical literature to the American animals easily.

Their strange forms were displayed in drawings and paintings as symbols of all that was exotic and alien, wild and fearsome. They were compared and identified with the fantastic beasts about which the Classics had talked, they were viewed as living ‘jigsaw puzzles’ composed of parts of other animals.

Living jigsaw puzzles.

There’s something to that, too. The ancestor of the turkey that ends up in the Roast Without Equal migrated from Europe to North America, where it developed into its modern form. Then it was brought back over by explorers, and raised and improved across the continent.

Every animal raised by humans is, in a sense, a living jigsaw puzzle assembled by global trade routes, market demands, technological innovations, and genetic accidents.

How we get a regular old turkey these days is much stranger than medieval chefs sewing together two different animals. For example, at any given moment, there are hundreds of millions of pounds of frozen turkey parts across the vast artificial cryosphere of refrigerated warehouses.

And not to make this point too strongly, but maybe these melanges, the cockentrices and turduckens, reflect something of the muddle of the human experience of the modern dynamic world. Turduckens just make sense to John Madden for some reason, no?

But still: why would anyone take the time to do anything like what we see in Tudor cookery, fantastical creatures aside? Another experimental food historian, James Materrer, has something of an explanation in his exploration of “incredible foods.” He draws on German historian Helmut Birkhan, who himself drew on legendary anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss (emphasis added):

The imitations of dishes and special presentations assume a deeper, almost philosophical meaning if we consider the theory of Lévi-Strauss, according to which the preparation of food constitutes one of the major culture-creating achievements of humanity, the cooking of the raw an act of establishing culture. In these dishes man transcends nature either by transforming the foodstuffs (e.g. cooked peas turned into a hare-roast), or by preparing them in a nobler or more artistic form, as is the case with the special presentations. The chef thus becomes a creator, like the painter who adds symbolism to his depiction of nature, who transcends nature by capturing the meaning given to it by God through his creation of meaning.

What I see is that the cook’s techniques could be seen as a metaphor for the power of the host. Think of it like the way the space program could be seen as a proxy for intercontinental ballistic missile skill. The spectacle reminds everyone of certain realities without requiring actual power to be exercised.

They did call the dishes subtleties after all (though the word had more the connotation of “clever” at the time).

Just as there is no one explanation for the bacon craze, I’m sure many motivations were at play for the chefs of the time: artistry, fun, competition, weirdness, technology, skill.

And most fundamentally, human beings are ridiculously, relentlessly creative. Given the resources, time, and context, we’ll just do crazy things.

Why? Because we are human and we can.