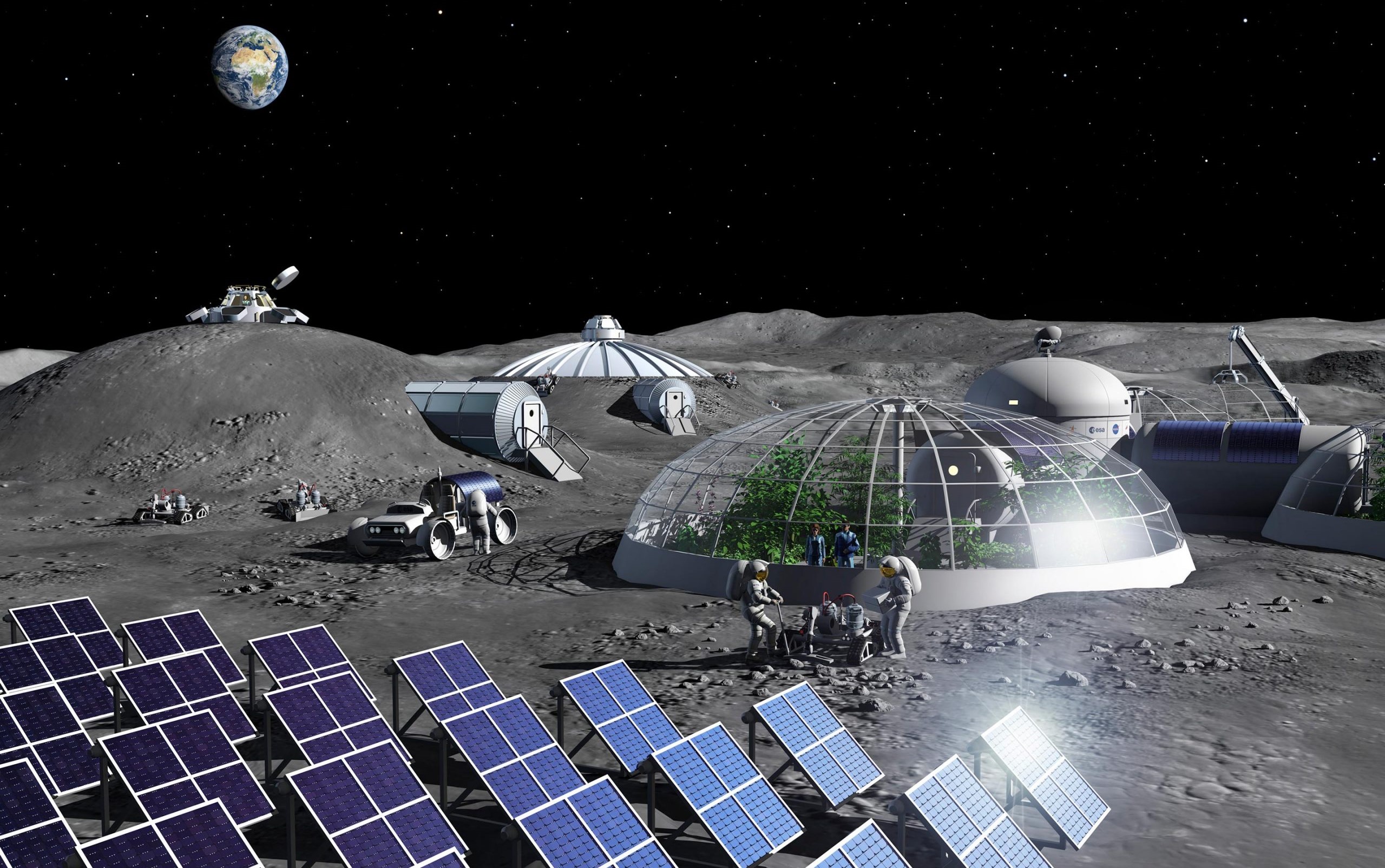

Along with advances in space exploration, much effort and money has recently been invested in technologies that might allow for effective space resource usage. And at the forefront of these efforts has been a laser-sharp focus on finding the best way to produce oxygen on the moon.

The Australian Space Agency and NASA agreed to send an Australian-made rover to the moon as part of the Artemis program, with the goal of collecting lunar rocks that might eventually provide breathable oxygen on the moon.

Although the moon has an atmosphere, it is relatively thin and primarily composed of hydrogen, neon, and argon. It’s not the kind of gaseous mixture that can sustain oxygen-dependent mammals like humans.

However, there is plenty of oxygen on the moon. It’s just not in a gaseous form. Instead, it’s locked inside regolith, the moon’s surface layer of rock and fine dust. If we could extract oxygen from regolith, would it be enough to support human life on the moon?

The breadth of oxygen

Many minerals discovered in the ground around us contain oxygen. And the moon is mostly composed of the same rocks found on Earth (although with a slightly greater amount of material that came from meteors).

The moon’s crust is characterized by minerals such as silica, aluminum, iron, and magnesium oxides. All of these minerals include oxygen, but not in the form that our lungs recognise.

On the moon these minerals exist in a few different forms including hard rock, dust, gravel and stones covering the surface. This substance is the consequence of countless millennia of meteorite collisions on the lunar surface.

As a soil scientist, I’m hesitant to use the term “lunar soil” to describe the moon’s surface layer. Soil, as we know it, is a magical substance that only exists on Earth. Over millions of years, a wider array of organisms worked on the soil’s parent material — regolith, which is derived from hard rock to construct it.

The result is a matrix of minerals which were not present in the original rocks. The soil on Earth has remarkable physical, chemical, and biocompatibility. Meanwhile, the materials on the moon’s surface is basically regolith in its original, untouched form.

One substance goes in, two come out

The moon’s regolith contains approximately 45% oxygen. However, that oxygen is tightly bound with the abovementioned minerals. We must expend energy in order to break such strong bonds.

If you’re familiar with electrolysis, you might recognise this. On Earth this process is commonly used in manufacturing, such as to produce aluminum. An electrical current is passed through a liquid form of aluminum oxide (commonly called alumina) via electrodes, to separate the aluminum from the oxygen.

The oxygen is created as a byproduct in this case. The main product on the moon would be oxygen, with the aluminum (or other metal) extracted as a potentially valuable byproduct.

It’s a pretty straightforward process, but there is a catch: it’s very energy hungry. It would need to be sustained by solar energy or other energy sources accessible on the moon to be sustainable.

Extracting oxygen from regolith would also require substantial industrial equipment. To begin, we’d need to turn solid metal oxide into liquid metal oxide, either by heat or heat combined with solvents or electrolytes. We have the ability to do this on Earth, but getting this apparatus to the moon — and generating enough energy to run it — will be a mighty challenge.

Earlier this year, Belgium-based firm Space Applications Services announced the building of three experimental reactors to enhance the electrolysis process of producing oxygen. They expect to send the technology to the moon by 2025 as part of the European Space Agency’s in-situ resource utilization (ISRU) mission.

How much oxygen could the moon provide?

That said, when we do manage to pull it off, how much oxygen might the moon actually deliver? As it turns out, quite a bit.

We can make some estimates if we ignore the oxygen locked in the moon’s subsurface hard rock material and only consider regolith, which is easily accessible on the surface.

On average, each cubic meter of lunar regolith contains 1.4 tonnes of minerals, including around 630 kg of oxygen. NASA says humans need to breathe about 800 grams of oxygen a day to survive. So 630 kg of oxygen would be enough to keep a person alive for around two years (or just over).

Let us now assume that the average depth of regolith on the moon is around 10 meters and that we can extract all of the oxygen from it. That really is, the top ten meters of the moon’s surface would produce enough oxygen to support all 8 billion people on Earth for around 100,000 years.

This would also depend on how effectively we managed to extract and use the oxygen. Regardless, this figure is pretty amazing!

However, we do have it pretty well here on Earth. And we should do everything we can to protect the blue planet — and its soil in particular — which continues to support all terrestrial life without us even trying.