The war in Ukraine is a different kind of war. The size of the theater of operations, the number of troops and the technologies used in the conflict are markedly different from the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Ukraine is a true war of “dual use” technologies; commercial products are widely used by both sides. Consumer drones detect and track unit movements, Internet satellite maps are used to plan operational maneuvers, and commercial satellites provide Internet/communication services.

The scale at which “dual-use” technologies are being used should cause us to urgently rethink how the Department of Defense makes its purchases. We need to accelerate the acquisition process and allow new technologies to be developed, deployed and scaled quickly.

Problems with the defense industrial base

At the beginning of the war it became clear that the consumption of ammunition, artillery and missiles was exponentially higher than what Ukraine and the United States were prepared for.

A senior Ukrainian military official was quoted as saying that the country was firing between 5,000 and 6,000 shells a day; Russian spending is even higher.

Meanwhile, annual US production of 155mm artillery shells is about 80,000 shells, or enough for two weeks of combat. The Wall Street Journal quoted a US defense official as saying that the US artillery shell inventory is “uncomfortably low”.

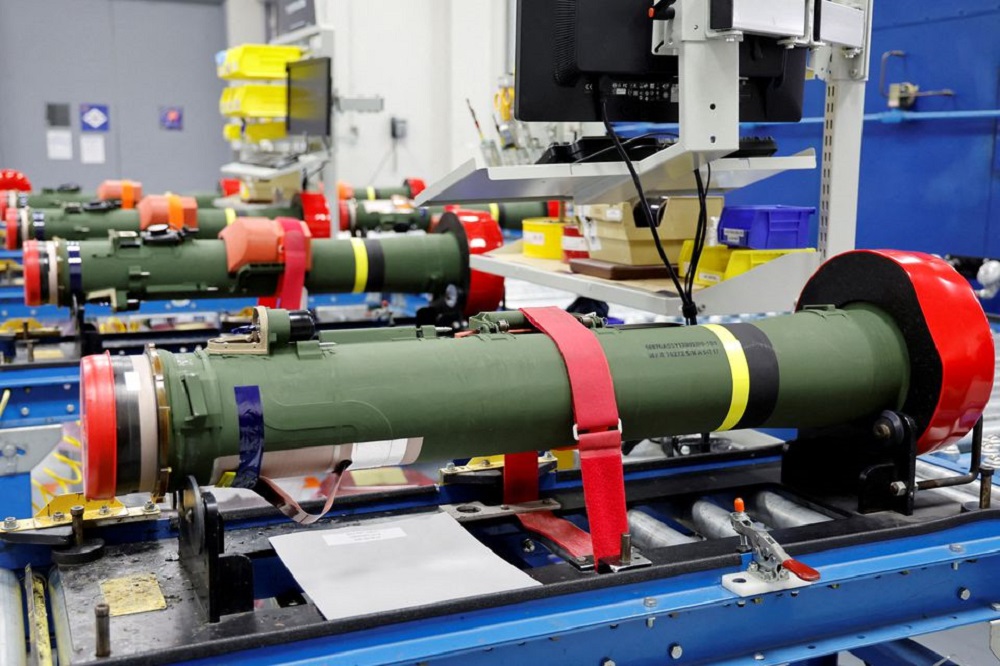

Artillery shells are not the only problem. Forbes noted that there are reports Ukraine used 300 Javelins missiles in the first week of the war; US annual production is 2,100 missiles or enough for seven weeks of fighting.

In 2018, the Department of Defense hinted at these problems in a report on the state of the nation’s defense industrial base.

The negative effects of the shutdown and budget caps shocked the market and accelerated the downward trend in vendor counts, leading to an estimated 20% decline in the number of top vendors,” according to the report. “Improving the capacity of the industrial base would solve the problem in the short term, but in the long term the problem would persist. Once defense spending drops, manufacturing capacity will follow. It is not wise to have an industrial base that is in a constant state of tension, either facing a rapid need for expansion or a rapid need for downsizing.

The long-term solution to the problem is to change the procurement process. In particular, the process needs to be accelerated, creative solutions encouraged and innovation rewarded.

Redesign acquisition

Currently, the DoD procurement process is governed by a checklist of detailed requirements.

Instead of checklists, the procurement process should define: capacity, key performance requirements, operators, and quantities needed.

For example, a portable anti-tank system must penetrate a Russian T-90 tank, have a range of 5 km. It will be used by front-line troops, and 2,000 units are initially needed.

Second, to encourage innovation, the Pentagon should approach the development of each new product like a blank slate. Third, the prototype demonstration should be scheduled 12-18 months after the project start date, and fourth, all submitted prototypes should be performance tested and evaluated for cost-benefit.

Finally, the DoD should purchase the initial amounts from the “winner.” Perhaps counterintuitively, the Pentagon should avoid awarding R&D contracts or grants and only start sharing lessons learned once the product is in field testing.

Most likely, Pentagon development grants will end up going to companies specialized in attracting them, meaning current providers would outperform newcomers. We want companies to compete on their product development skills and not on their ability to manage the procurement process.

This loosely defined and streamlined process will allow the industry to develop creative “dual-use” solutions. For example, the next anti-tank weapon might not be a shoulder-launched missile, but a commercial drone or directed energy weapon. It is also very likely that the next system will be developed by a start-up or non-defense company.

Tight lead times should favor products and production processes that can scale quickly, solving the long-term problem of having enough capacity online in case of need. Guaranteed purchase orders should make Defense Department projects financially attractive to investors. Lastly, having a clean slate would solve the “better horse” problem, where new products offer only incremental improvements.